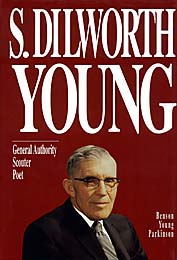

S. Dilworth Young

General Authority, Scouter, Poet

by

Benson Young Parkinson

Copyright 1994

To Dil, Gladys, Young Dil, and Leonore.

Foreword

This book is based largely on interviews of Dilworth’s friends and family. As anyone

knows who has gathered oral history, facts become skewed, sources contradict themselves and

each other, things come out in the wrong order, people imagine, confuse, and forget. The same

holds for personal histories and journals. I have picked these stories, knowing that any given

detail might be wrong, because the gist is there: This is how people saw S. Dilworth Young; or

This is his voice in telling his own story. Sometimes oral history puts forward less of history, but

more of the man.

This book has been over ten years in the writing. In that time, the old Young home on

24th Street in Ogden, which Gladys called Rosemont, has burned and been rebuilt according to a

new plan. I regret to say that in that time too, many of those to whom this book would have

meant most have passed on.

I decided to write this book after reading my grandfather’s unpublished Life Story. Those

one hundred and thirty pages, with his military and mission diaries, could have formed the core

of Dilworth’s best book, but he never wrote it. My book would not have been possible without

the cooperation of Dilworth’s widow, Hulda Parker Young, who gave access to these and others

of his papers and recordings, suggested people to interview, gave several important interviews

herself, allowed me the use of personal materials, and criticized the manuscript. Leonore Young

Parkinson, Dilworth’s only surviving child and my mother, also made available primary sources,

helped develop numerous contacts, gave repeated interviews, and criticized early drafts. Some of

these memories were painful for Hulda and especially Leonore, which makes their contributions

doubly valuable.

Carlie Louine Clawson Young, Dilworth’s mother, left a personal history. Gladys Pratt

Young, Dil’s first wife and my grandmother, was a haphazard journal keeper, but her letters

during their courtship survive in Dilworth’s scrapbooks. She also left charming stories of her

childhood, which with others of her writings came to me through Mary Pratt Parrish, her niece.

Louine Young Cromar, Dilworth’s sister, shared materials on Dilworth, including a transcript of

some of Dil’s stories, her own personal history, letters, excerpts from their late sister Emily

Young Knepp’s diary, and Emily’s personal history. Much credit goes to Dilworth Blaine

Parkinson, my brother, who interviewed Dilworth or taped him telling stories on five different

occasions in 1977-78, and who also filled two 90 minute tapes with his own memories. Other

family members who helped include Dilworth’s brother Hiram, his sister-in-law Louise Young,

son-in-law Blaine Parkinson, and grandchildren Charlotte Parkinson Fry, Robert Alan Fry,

Annette Parkinson, and Wendy Parkinson Asay. Relatives on the Young side: Harlan Y.

Hammond, Phyllis Wells, and Gene F. Deem; on the Pratt side: Boyd and Mary Pratt Parrish,

Berta Pratt Whitney, Gerda Pratt Haynie, and Stanley and Juliette Cardon. From the Parkers:

James and Giana Nielsen.

For memories of Dilworth’s early life, I thank his lifelong friend Merlon L. Stevenson. R.

Lamar Barlow filled in background on the 145th Artillery and battle in World War I. Missionary

friends who contributed valuable information include Francis G. Wride, Dilworth’s companion in

the backwoods of Louisiana and in New Orleans, and Alexandre E. and Ethel Kane Archibald,

Bessie E. Kelly, and Grace Valentine Price, fellow workers in the office in Independence,

Missouri. Leland P. Draney, a previous mission secretary, provided documents and took the time

to type out answers to my lengthy list of questions on that calling’s duties. For memories of Rey

L. Pratt I thank Hugh Barnes and Dell B. Stringham.

Ogden friends who gave me stories include Delora Hurst, Myrene Brewer, Mary Wilson,

Maggie Gammell, George Frost, Heber S. Jacobs, Lloyd L. Peterson, Martha Johnson Barney,

Betty Peterson Baker, Ben H. Davis, Helen Grix Plowgian, and Margaret Wilson Barlow. Ena

Barnes, and Dorothy West, Gladys’ pageant aides, were also very helpful. Among scouters I

thank Eden W. Beutler, Percy W. Hadley, Paul S. Bieler, A. Russell Croft; also the following

scouts: Jack Davis, George H. Lowe, Thomas M. Feeny, James N. Oka, E. LaMar Buckner, Don

Buswell, Max Wheelwright, Worth Wheelwright, and Wally Brown. The Ogden Standard-

Examiner, in helping my grandfather publicize his program, in the process preserved his

activities for posterity. Richard Sadler steered me toward Lyle J. Barnes’ helpful master’s thesis

on corruption in Ogden. On this account too I must thank the Standard, also Cecil K. Parker, a

juryman.

The following New England missionaries helped: Truman G. Madsen, Oscar W.

McConkie Jr., Rex W. Williams, Blaine P. Parkinson, and D. L. Woodward. Boston students and

friends include John Hale and Olga Gardner, Richard and Mary Lou Harline, Talmage and

Dorothy Nielsen, J. D. and Barbara Williams, and Rosemary Fletcher. For his Salt Lake and Los

Angeles years I relied mostly on published and family sources. However, for their varied

contributions I wish to thank H. Smith Broadbent, Phyllis Peterson Warnick, Bruce R.

McConkie, Levier and Cynthia M. Gardner, Eb L. Davis, and Reid and Thelma Brown.

Thanks and apologies to all those who helped whom I have neglected to mention. My

thanks for secretarial assistance to my wife, Robin L. Parkinson, and to Charles Fry, also to my

father, Blaine P. Parkinson, for financial support in this project. Finally, I would like to thank

Covenant Communications and its managing editor, Giles H. Florence, Jr., for giving the family

the chance to present this story to the world.

- Benson Y. Parkinson

December 24th, 1993

About the Author

Benson Young Parkinson was born in 1960 in Provo, Utah, and raised in Ogden. He spent

1978 as a Rotary exchange student in Sydney, Australia. After filling a mission in southwest

France from 1979 to 1981, he graduated in 1985 from Brigham Young University with a degree

in Comparative Literature. He lives in South Ogden with his wife Robin and four children, where

he works full time as a writer. An avid hiker with an interest in computers and American Indian

culture, he serves as scoutmaster in the South Ogden 58th Ward.

Chapter 1

A Salt Lake Childhood

Origins

Seymour Bicknell Young, Jr. was born January 11, 1868, in Salt Lake City, Utah

Territory. As a young man he served a mission in England, returning early to attend the

dedication of the Salt Lake Temple in 1893, then serving a second, shorter mission to New York.

Seymour was a striking man, lean and broad-jawed, with a rich, baritone singing voice. He sold

wagons and later automobiles for the Consolidated Wagon and Machine Company, and did well.

Once he sold a hundred small white Buicks in a hundred days. As a publicity stunt, he and a

mechanic drove one to the top of Ensign Peak before there was a road. He would race the engine

and lurch forward, then the mechanic would rush to block the wheels, then he lurched again, and

so on to the top. Seymour was the eldest son of Seymour Bicknell Young, Sr., who as an infant

survived the Haun’s Mill Massacre. He too served a mission in England, taking part in the

eastbound missionary handcart company of 1857. Seymour Sr. studied in the east and became

doctor to his uncle, Brigham Young. He served many years in the First Council of Seventy, like

his father, Joseph Young, one of the original Presidents, and Brigham’s brother.

Carlie Louine Young Clawson, known as Lou, or Lulu, was born in Salt Lake on July 28,

1869. Family lore says once a middle-aged apostle gave her a lift in his buggy and in the course

of the ride asked her to be his plural wife, but that she turned him down. Lou was softly pretty–

she and Seme made a striking couple–but was shy in company and retiring in the family. Lou

was a daughter of Hiram B. Clawson, a pioneer entrepreneur with a dramatic bent, whose career

included managing ZCMI and the Salt Lake Theater. Dilworth remembers the Clawsons always

laughing. “They seemed immune to sorrow, they joked, they dramatized, they had physical fun.”

Lou’s mother, Emily Augusta Young, was a daughter of Brigham Young by Emily Partridge,

Bishop Edward Partridge’s daughter and a plural wife of Joseph Smith. That made Lou

Seymour’s second cousin through John Young. In the days of polygamy, with its large families,

this was not uncommon. Lou was old enough to have memories of Brigham, who called her his

little beauty. Once when she was playing on the front steps of the Church Office building, he

passed by and noticed her with a great mouthful of gum. “Lulu, I wish you wouldn’t chew gum,”

he admonished her. “It is not a nice thing to do.” She writes, “It made a great impression on me,

for since then I never chew it or like to see anyone else indulge.”

Seymour Dilworth Young, Seymour and Lou’s second child and first son, was born

September 7, 1897, at 5:00 a.m., in a house at 83 Canyon Road, Salt Lake City. The house sat on

the west side of the street on a spot where 2nd Avenue now cuts through. “My father,” he tells,

“ran for the doctor. He had to go clear up on 4th East, to where our grandpa had his horses. And

then he lost the key to the barn, and they had a dickens of a time, but they finally got a doctor

there.” “My mother,” he writes on another occasion, “tells me that I cried constantly from the

time I was born until I was about six months old, that I wore out her and half a dozen nurses. She

also said that after that I would sit on her lap with my feet against her abdomen and constantly

push, so that it was an effort at all times to keep me on her lap.”

One of Lou’s lullabies, a version of “A Frog Went A-Courting,” goes:

A frog he would a wooing go

Hi-ho, says Rolly

And whether his mother would let him or no

With a rolly polly gammy spinach

Hi-ho, says Anthony Rolly

So off he set with his opera hat

Hi-ho, etc.

And on the road he met with a rat

etc.

The family lived for a time in a home on the west side of Liberty Park. Dilworth’s early

memories include watching Hiram, his younger brother, toddling across the street and into the

park with their mother in pursuit. Dilworth, at two-and-a-half, worried she wouldn’t be able to

catch him. The family moved to 4th South, then again to 560 East 6th South. Dilworth

remembers dolls and dress-up with his older sister Emily. Emily describes their mother putting a

blanket over the dining room table for them to play house, Emily and Dilworth taking the roles of

momma and papa, with Hiram for the baby. Dilworth also remembers playing under the table

when his mother was preparing food for a party. Dilworth, pretending he was in a tent, would slip

out and snitch a pickle when his mother left the room. He mentions a neighbor boy small enough

to crawl into his family’s chicken coop by the hens’ door. He would hand out an egg, which the

two of them traded for candy at the store. The Youngs had a sandpile “on the west side of our

house in the morning shade and there I spent a lot of time. I remember thinking that sandpile

playing was the greatest objective in life.” He mentions being afraid of thunder and lightning,

hiding himself in his bed and covering his ears with his pillow. “One day I sat on the porch

against the door during such a storm and discovered that I did not need to be afraid.”

Dilworth says his father was “a very good pianist, and he had a fine singing voice.” He

says, “In those days there was a lot of singing going on in our parlor. Father . . . gathered about

him a lot of people who liked to sing. They had happy, good times, and I enjoyed listening to

them.” Seymour originally intended to become a musician and would have taught piano and

voice. “Grandma talked him out of it, foolishly. Ought to have let him do it. He’d have been

happy. That was his natural bent.” Seymour was active and busy in the 2nd Ward, holding

positions such as Sunday School Superintendent and Chairman of the Music Committee. Hiram

says the Bishop told him at one time he might as well be bishop, as much time as he spent doing

church work. One year Seymour put on a minstrel show for the ward. The normal pattern was to

have a semi-circle on the stage, with two “end men” and the chorus, all in blackface. An actor

without blackface, called the interrogator, sat in the middle and asked questions, while the two

end men cracked jokes. Seymour’s innovation was to make it a ladies’ minstrel. Lou sang in the

chorus, the only time Dilworth remembers her participating in any public performance or

meeting of any kind. Hiram and another boy did a dance called “The Golddust Twins in Clogs.”

Golddust was a brand of powdered laundry soap with the twin girls on the label. Dilworth

remembers the black underwear and greasepaint and yellow skirts and wigs and being so jealous

he hardly knew what to do with himself. “I learned to do the clog. I said, ‘Daddy, I can do this.’

And he said, ‘Well, let’s see you. So, what are you going to sing?’ I said, ‘I’ll sing, I’m a Yankee

Doodle Dandy,'” and he sang and danced but his father still would not put him in the show. Dil

remembers the Danish members in the 2nd Ward.

In fast day meetings, testimonies were often unintelligible to me as the Saints struggled to

testify in English, their new tongue. In Sunday School the room was divided into

classrooms by green curtains hanging from wires overhead. If I was not interested in what

my teacher was saying, I could choose from five other classes, all of which I could hear. It

was always interesting to try to solve the problem of the identity of the boy who kept

poking me in the back through the curtain at my rear.

The Young children went through mumps, measles, rubella, whooping cough, and

perhaps scarlet fever. Likely they had rheumatic fever as well, for both Dilworth and brother

Scott Richmond developed heart trouble later in life. “Grandpa Young was the doctor. I

remember Mother putting some chairs together, putting a sheet over them, and we three children

crouching under and breathing fumes of menthol tinged with turpentine and a drop of carbolic

acid.” The whooping cough developed into pneumonia in Dilworth’s infant sister Florence, and

she died. “I remember seeing Mother being led from the room by Father. She was weeping

violently and Father was trying to comfort her. I remember going into the room and seeing my

tiny baby sister lying like a wax doll on the lap of the nurse. It seems to me they had a funeral at

the house–at least I remember a lot of people being there.”

At Christmas time Dilworth tortured himself trying to figure how Santa Claus got through

the six-inch stove pipe, around the kinks, into the stove, then opened the door from inside to get

out into the dining room. (Christmas morning was held in the dining room, the parlor being

reserved for formal occasions like Christmas dinner, Sabbaths, ward teaching visits, and

“lickings.”) One Christmas, probably when he was five, Dilworth pined for a wood jigsaw puzzle

he had seen in a store window, showing an old-fashioned, horse-drawn fire engine. With the

horses running and the dogs barking underneath and the smoke billowing out from the fire

making the steam to pump the water, Dilworth couldn’t imagine anything more exciting. His

mother insisted they eat a bowl of mush in the dining room before they could open their presents,

“to fortify us against the candy, I guess.” Dilworth finished and went out to the dining room to his

chair to empty his stocking, which besides the candy held an orange, a novelty in those days.

Then on to the presents–a new clipper sled, which Dilworth says at that time beat flexible flyers

“all hollow,” and a smaller package. Dilworth recognized it immediately as his puzzle.

Their father let the children play with their toys for about an hour, then approached them

and said, “Well, Boys and Girls, you remember that Danish family over on 7th South?” These

were the Olsens, a immigrant couple with children more or less the same ages as the Youngs.

Dilworth remembers not liking the boy his age. “His dress, smell, everything was different,

strange and Danish.” He admits to having had a “little tiff” with him a few days before. Seymour

went on, “Now, we’re going to take them our Christmas dinner. Are you willing?” The children

agreed, though without really understanding the implications. Then his father said, “I want each

one of you children to decide to give your best toy, the one you like the best, to those children.”

So it was decided. They would leave at noon.

I had an awful fight with myself. I sat there and looked at that clipper sled, and I wanted

to give it to him, and I wanted to keep my fire engine puzzle, but Father said, “Give him

the one you like the best,” and I didn’t want to disobey Father, so finally I decided I’d give

that boy my fire engine puzzle.

The family made their way down the back alley, Father carrying the turkey, Mother the

dressing and gravy, the children toting pots of potatoes, sweet potatoes, plum pudding and dip,

and cranberry sauce. They knocked on the door of the Olsen’s tiny two-room house. Dilworth

remembers a table and two chairs, but no other furniture. Seymour said, “Brother Olsen, we

brought you some Christmas Dinner.” He didn’t understand his English, but Seymour gestured

and got the idea across. Brother Olsen had them in. Seymour demonstrated how to carve the

turkey, and Lou showed how to serve up the dressing and what went with what. Dilworth

remembers a single bucket of coal and a small fire in the stove, barely enough to take off the

chill. Seymour said, “Alright, now, Children, it’s your turn.” Emily gave the girl her age her large,

bisque doll. Dilworth walked up to the boy and said, “Here!” The boy grabbed the puzzle just as

brusquely as it was offered, without saying a word. Hiram toddled over with his gift and said,

“Here’s sum’n.”

And all the way home, I was walking on air. I don’t believe my feet hit the ground once. I

don’t know why, I just suddenly realized what giving was. And to give our best and to

give all we had was the finest thing we could do . . . When we got home, I thought maybe

my mother had a Christmas dinner tucked away somewhere, but she didn’t. She opened

up a can of beans and we had bread and butter and beans for Christmas.

School Days

Dilworth remembers his mother as sickly, and he asked her about it when she was old.

She said it wasn’t a matter of disease. “I had seven miscarriages. If I’d had all the children I had

conceived, I’d have had thirteen children.” As it was she had six, of which five survived. The

Youngs hired a woman to help with housework and tending, and she boarded with the family.

Emily says, “She took pains with Dil and me to teach us to read before we ever started school.

We could read the easy words in the newspaper when we entered the first grade.” She tells of

being asked to stay after school with Dil after only a few days (this would have been at the

Sumner School, on 3rd East between 6th and 7th South), and standing fearfully before the

teacher’s desk, who asked them to read from a second grade reader. Both could do so easily, and

on the basis of that, both were promoted to the second grade. Dilworth talks about reading in his

history, but does not mention the incident. He writes he was a year behind Emily in the fourth

grade, but then of the two of them graduating together. Given family circumstances, it seems

likely one or both lost or gained a grade or two.

One thing is certain–Dilworth read well from early on, and he loved to read. Emily

remembers him kneeling before a stuffed chair with a book on the seat for hours at a time.

“Father would get out of patience when he wanted Dil to get a scuttle of coal from the shed for

Mother to put in the range, for I can hear him say, ‘Just a minute,’ but he never could find the

place he could leave his book, and Father would have to pull him up and see that he did it.” His

Uncle Lee (Levi Edgar Young) gave him a six-volume Horatio Alger set, the “Ragged Dick”

series, and he read these and others. Once he gave him a year’s subscription to “Cosmopolitan”

(at the time a literary magazine). “I could not understand what I read, but I tried. It was my

magazine, and I did my best to live up to it.” Lee introduced him to “The Last of the Mohicans.”

“Ever after that the Delawares were my Indians and the Iroquois were my enemies. I read the

whole series by Cooper.” He read classics and the Standard Works and every religious book he

could find. Emily speaks of him spending hours in “Grandpa Young’s huge library . . . Dil would

go to see them early in the morning and they would never hear from him till late in the day. He

was curled up in a big comfy chair in the library.” Once his father promised to give him any book

in his own library if he would read it. He chose one called “‘Character–Smiles.

I wanted to smile so I started. I didn’t understand any of it except the “and’s” and “it’s” and

small words. Later–long later–I found it among my books and correctly read the label,

“Character–by Samuel Smiles”, an essay for the middle aged, but Father kept his word

and gave me the book.

Dilworth stayed out of school at times to help around the house. He remembers

alternating with Emily to help take care of Richmond when Louine was born in December 1908.

“We washed the clothes in a machine which we turned with a handle on a wheel . . . we changed

beds and mopped floors, and we swept the Navajo rugs every Saturday which were in our

linoleum-covered living room.” On another occasion, he adds, “I learned to make bread. We had

a [universal] mixer and Mother would tell us how to do it from the bed.”

Dilworth liked school, but he was “bedeviled by a boy named Sigurd Simpson, a dirty

fisted boy of about eight. I was so scared of him that my life was miserable. I invented excuses

not to go to school. Sickness feigned, hiding my cap, or losing my book until it was past 9:00.”

His father finally complained to the principal, who told him, “Seymour, you baby your boy too

much. He’s got to learn to fight his way, and until he learns he won’t be much good.” This took

him aback. That night he told him if any boy licked him he could expect a licking when he got

home, “and that I was to learn to stand up to the other boys.” He bought him a pair of boxing

gloves and arranged for his Uncle Shirl Clawson (later a Hollywood cinematographer) to give

him a few boxing lessons. Dilworth does not say whether they helped, only that the family

moved soon after to a house on the southwest corner of 9th Avenue and -C- street, across from

the LDS hospital–this would have been in early 1907, when Dilworth was in the fourth grade. “I

suppose that ended it, for I had no trouble thereafter.”

“I enjoyed the school–no boys bothered me and I had little trouble except with arithmetic.

I was not a good analyzer. English, history, spelling, grammar, were no trouble.” The class at

Lowell Elementary, where he now attended, put on several dramatic productions, including the

Iliad and Odyssey and Alice in Wonderland. “I was the Cheshire Cat because I have such a broad

grin. I was proud of the part; and when we presented it to the parents, I about split my mouth in

two trying to grin as broad as that cat is supposed to have done.” Dilworth and his friends were

throwing rocks one day in the schoolyard. Dilworth aimed, but the rock went off at an angle,

sailing up to the second floor and crashing through the window of his own fourth grade class.

Red-haired Mrs. Burmister came to the window. Dilworth, paralyzed with fear, suddenly found

himself alone in the schoolyard. All the others ran. She said, “Dilworth, did you break this

window?” Dilworth, with the directness that always characterized him, said, “Yes, Ma’am.” She

called him in and took him to the principal, William Bradford. When he asked, Dilworth

answered, “Yes, Sir, I broke the window. I didn’t mean to. This rock slipped out of my hand and

got going the wrong way.” He told him he would have to take it up with the school board.

Dilworth passed an anxious weekend, then on Monday “I was called in and told that, because I

had told the truth and had not run, I would be excused from paying for the window. That was my

first experience in honesty being rewarded, and I have never forgotten it.” Dilworth recalls Mrs.

Burmister trying to honor him with a kiss.

After Hours

Childhood games Dilworth remembers include kick-the-can, pom-pom-pull-away, duck-

on-the-walk, mumble-peg, marbles, hopscotch, jump-the-rope, and tippy-cat. For this last, “one

whittled the cat from a broom handle. The bat was a flat paddle. One struck the edge of the cat,

flipping it in the air, and while in the air, striking it with the bat, driving it as far as he could.”

The opponent would allow a certain number of bat lengths. The driver could take them or

demand more, in which case they measured. “If the driver was right, he got that many more

points.” Seymour bought the children a donkey while they still lived on sixth south. Dilworth

remembers mostly the older boys in the neighborhood stealing it from their yard and his mother

going after them. Once it balked on a set of streetcar tracks. Lou pulled and Dilworth and Emily

beat with sticks, but they could not get it off. Finally, “the car came to a stop, the motorman and

conductor and a passenger got off and pushed the donkey off the tracks and went on their way,

much to the amusement of everyone on the car–and to Mother’s embarrassment. I was

embarrassed too.”

Dilworth played with the Marron boys, Ben and Hen, back fence neighbors, “Irish kids,

tough and mean, [who] liked to fight all the time.” Once Hen and Lewis Larson ganged up on

him. “I figured, well now, I’ve got to get Lewey out of this, because the Marron kid was quicker

than he was, so I just kept hitting Lewey on the nose until he started to bleed, and that fixed him,

he didn’t need to go anymore, and Hen ran.” The Marron boys and other neighborhood kids stole

the Youngs peaches summer after summer, until Seymour got the idea of hiring the Marrons to

watch them. “‘You can have what you want to eat, Boys, but watch it so that the other boys don’t

take it.'” That did the trick “They, when on their honor to watch and protect, did not feel they

should steal. It proved a good way to handle boys.” When a streetcar line was laid down along

9th avenue, the LDS hospital put in a sidewalk to combat mud on visitors’ shoes. Dilworth,

Hiram and the Marrons waited until that evening when the cement workers went home and

carved their initials in the cement–SDY, HCY, BM, HM and LCY for little sister Louine. There

they remained over seventy years for him to read as an old man.

Dil and Hi also played with George Cannon Young, their cousin, who lived nearby. Once

they got into some new houses on C street above 9th Avenue and played cops and robbers. “Our

cap pistols echoed nicely.” The owners arrived without notice. Hi and Cannon were caught, but

Dil “went up over the hill like a frightened deer. That night Father told me I would probably have

to go to the juvenile court. I went through the tortures of fear of going to court–whatever it was it

had a fearsome sound.” Seymour let his boys stew two or three days, then told them he had

gotten them off with a promise never to do it again. “We were entirely unconscious that we were

doing wrong, but we did climb to the attic through a hole in the ceiling of a closet–dirtying the

plaster. I suppose Father paid for the damage.”

Dilworth mentions smoking with Hi and Cannon. “There was lots of smoking done in

those days by nearly everybody . . . We managed to find some old big corn cobs, and we thought

it was kind of cute to make corncob pipes.” For tobacco they used cedar bark from the back

fence, which Hiram remembers made them sick. Dil says, “We sat there pondering the centuries

and tried to decide where babies came from. Cannon held for the stork and I held for the doctor

and we were both wrong.” Their father found out and confronted them before the family, telling

them if they were going to smoke, to do it in the open. That apparently put an end to it. Dilworth

writes of himself, “My bump of honor and honesty must have been well developed. I didn’t need

to be told more than once that a thing was not right and I stopped doing it.” Hiram tells of his

father offering each one hundred dollars if they would refrain from smoking and drinking and

keep themselves clean until they were twenty-one. When the time came he had no money and

could only tell them he would make it up to them. Hiram said never mind, that they ought to pay

him a hundred dollars. For all that, Seymour smoked–away from the family–and Dilworth

remained aggravated and disturbed into old age after having found him at it one day.

Dilworth speaks of his father as kindly but nervous and strict. “I always thought Father

was fair with us most the time. He punished quickly, he had a quick temper, and he spanked us,

oh, yes, you bet . . . [But] he saw what we needed . . . Father understood us and he got us things

to play with.” He says, “when we wanted to play, he made us a little ball diamond outside and

bought a ball and a bat, and showed us how.” The diamond extended between their house and the

east-west ditch (which they sometimes dammed for swimming) about seventy-five feet away.

“We managed to make balls or find an old ball and knit a cover for it if the horsehide was

irreparable.” Seymour would not let them “play sides” on Sundays, but allowed them to play

“rounders.” “I remember one time I knocked a home run through our . . . dining room window,

right almost in the lap of the bishop, who was calling on Father.” Dil says the bishop used to

walk around the block to avoid seeing them on Sundays and having to tell them to stop. After the

streetcar line pushed through their field, the boys played on another patch of “not-too-flat land”

below 10th Avenue and between -B- and -C- Streets. At one time they had a team and coach.

“We persuaded our parents to buy us uniforms made of outing flannel. The uniforms were flimsy

but gave us a real professional look. The cost was one dollar each . . . Every Saturday in the fall

and spring it was either football or baseball.”

They sledded in winter, coming down the hill and over a footbridge crossing the ditch, the

ground dropping away on the other side. “Sometimes we could leap three or four feet. Our bellies

would be sore from the pounding when we hit.” Riding in the Avenues, “we got as far as we

wanted to go.” Boys commonly “hooked” rides on the backs of grocery wagons. The wagons

were reinforced with steel supports on the sides. The boys would pass a long rope through these

and hold on while being pulled on their clippers. They steered by pulling on one end of the rope

or the other. When they got tired they dropped off. Another type of sled was called a schooner,

large enough to hold a dozen people or more. “They’d have a horse pull that thing up to the head

of Federal Heights,” (the Avenues were too dangerous for schooners), “and then they’d all get out

and turn the thing around and . . . slide down around those curves on Federal Heights into South

Temple. They’d go as far as fifth east before they stopped.”

It may have been the schooners that inspired the four-man coaster wagon Dilworth’s

father built.

It was the only thing of its kind ever invented. Otto Oblad the blacksmith made it. It had

real buggy wheels cut to about twenty-seven inch diameter. The steering was a bicycle

rim run by a sprocket and chain beneath. It had a brake like a real wagon. We used to start

at 10th Avenue and ride to Grandmother Young’s on [48 South] 4th East. Then we would

have to push it home.

Or they could leave it there until the next day, or the day after, as they often did. Hiram says,

“Father was wise. He knew where we were. He knew we were coasting or else pushing, mainly

pushing.” Dilworth agrees. “No toy ever used up more boy energy than that coaster . . . We were

never any trouble at home.” Not that there wasn’t trouble to be gotten into coasting. The wagon

could have upset. The spokes of the wheels were uncovered and could have broken hands or feet.

Once, he writes, “Hi and I and Cannon . . . conceived the idea we’d really like to have an

adventure.” The three of them pushed the wagon as high as the Veteran’s Hospital. Dilworth

steered, Cannon held onto the middle, and Hi worked the brake. Down they came, “lickety-split,”

over stones and sagebrush and molehills. “That thing bounced, cavorted–we hung on for all we

were worth. It’s a wonder we weren’t killed.” They turned onto the cement by the hospital “going

about thirty-five miles per hour . . . When we ended up at Grandma’s we were limp with excited

exhaustion.”

The boys finally discovered where they could ride with less effort. Starting on -A- Street

and 1st Avenue, they could coast east to -D-, then to South Temple, then back to -A- Street.

Dilworth calls it “perpetual motion”–seven blocks coasting for one block pushing. Of course it

was a steep push. Dilworth says the wagon took four or five kids to get up a hill when he first

started, but that as he got older and heaver, he could finally push it from South Temple home

alone. “That was my great thing.”

Seymour paid forty dollars for a red Durham cow with the left front and back teats joined

together, forming one large teat with two holes. The seller claimed she milked faster that way.

“We children fell in love with her and proudly led her home.” The double teat did give two

streams, but proved hard to work, and before long the milk began to come out bloody. “Father

went back to the man and told him that he had sold the cow under false representations and asked

for our money back. The man just laughed and told Father that he should be less naive.” With no

money for another cow, they used the milk from the good side. Hi brought in the milk dirty two

or three times, with some story about how it got that way. “Mother decided that we couldn’t keep

that up, so Hi was taken off the milking list. Years later he confessed to me that he had thrown a

handful of dry barnyard manure into the milk each time to get out of milking.” After about a year

Seymour sold the cow to a butcher. “It about broke us up, for we had learned to love that old red

cow. She surely was gentle and kind.”

The Youngs attended the 18th Ward on -A- Street above 2nd Avenue. Dilworth writes of

walking with Cannon and Hiram each Monday night to priesthood meetings as a deacon, also

Sunday mornings to “pass” in Sunday school and again in the evening for sacrament meeting. “I

used to envy the teachers who could carry the silver pitchers for refilling the silver goblets. These

were passed from mouth to mouth.” Hiram speaks of collecting fast offerings in kind and

delivering them to widows in the ward. John D. Giles, the deacon’s teacher, gave the boys pencils

and books and had them write down points for attendance and participation. Dilworth won a

prize when he was deacon’s president, “a boy’s history of ‘Abraham Lincoln’ by a man named

Morgan. I read it altogether about ten times in the next few years.” Dilworth thought highly of

John Giles, “who made the business of being a deacon seem very real.” Brother Giles writes of a

presentation Dilworth made on behalf of the deacons before meetings were adjourned for the

summer. “Dilworth arose and said in a rather commanding tone, ‘Brother Giles, we would like

you to stand right here.’ I followed instructions. Then I listened to one of the most carefully

prepared and appropriately presented talks I have ever heard from a boy.” Dilworth then

presented him with a book of poems by Tennyson.

Dilworth says, “I can remember that I wanted to learn and was very much annoyed by

boys who wanted to disturb. I can’t remember wanting to do wrong during that period. I heard of

other boys and their mischievous acts and used to wonder why they wanted to be that way. But

for myself, I didn’t want to, nor did Cannon Young or Hi.”

Most of the land north and west of the Young home was wild, still, and the boys liked to

play in the hills. “Cannon Young and I would get the fever to build underground houses. And so

every summer we would go over the rim of the canyon fifty feet or so and start to excavate.”

They heard of successful underground forts belonging to rough boys by the sand pits above -K-

Street, but they never managed to get theirs covered. “We did not have the money to buy old

lumber to roof them over and we would not steal any, so the holes were dug and the energy

spent–with loss of interest when we could not complete them.” Once in March Cannon and

Dilworth went on an overnight camp in City Creek. They packed two quilts and enough canned

food for a week, rolling everything in a wagon cover to be used as a tent. Each boy took an end

and they started out for the new road cutting into City Creek from 11th Avenue. “The farther we

staggered with our food, the more scared I got–and homesick. So I began to fake a stomach ache.

By the time we got to the place where the road bends to go toward the State Capitol I insisted on

going home.” By now the sky was black and low with an approaching storm. “We staggered

home with our load, much to Cannon’s disgust with my babyness, and got there just at dark and

just in time for supper. Father was just organizing a searching party for us.” It snowed eight

inches that night.

Cattle from the city roamed in the hills, which were covered in sego lilies. “We learned to

recognize them and dug the bulbs for spring salads. As I look back, they seemed inexhaustible,

but they are all gone now.” Seymour bought Dilworth and Hiram a repeating .22 Winchester rifle

one Christmas. “Every Saturday for about six months Father took us up on the hills in back of

our house . . . and taught us how to carry the gun so we couldn’t kill each other, how to shoot it,

how to never shoot at wrong things, target practice only on tin cans, never shoot at animals or

birds . . . before he let us take it out alone.” Dil admits, “I think I lorded it over Hi by carrying it

more and telling him when he could shoot, but he didn’t seem to be very resentful.” They never

really hunted with it, though once they took a pot shot at a bobcat.

When Dil was ten, a boy named Clarence Olsen was showing him and Hiram and Cannon

his mail-order Sears .22 pistol at the edge of City Creek Canyon. The gun’s spring was broken, so

he had stretched a large rubber band around the trigger guard and hammer. Clarence was

demonstrating how Buffalo Bill shot, pointing the gun in the air, then aiming into the canyon,

pulling the hammer back and letting go. The boys were standing in a half-circle facing the

canyon, Dilworth opposite Clarence.

All of a sudden my hand went numb. I looked down and saw an ever-larger spot of red on

my white shirt. I yelled, “I’m shot,” and headed for home as fast as I could go. Over the

back fence “belly buster” place, which Father had fixed to give us faster egress and

ingress to our lot, Hi went. He had for once been faster than I. Into the house, “Dil’s shot,

Dil’s shot!” Mother came out. The doctor came and soon discovered the bullet had gone

through the arm and out, missing the bone and arteries, but ticking a nerve–which

numbed my hand. The angle from which it was fired was such that it passed in front of

my breast and into my arm. One-sixteenth of an inch to the left and I would have been

shot through the heart. For three days I was a hero–then I was just commonplace–just

another accident. I have often thought that the Lord must have had some purpose in my

not getting the full load in the chest.

Clarence “ran like a rabbit up the canyon,” finally coming home that night. Seymour took away

his gun.

Mountain Dell

Seymour B. Young, Sr., in the early days, invested in four hundred acres at Mountain

Dell, near Little Mountain, where the reservoir now stands. For a time he “grub staked” it–

outfitting miners to prospect for a month at a time in exchange for half of what they found. He

eventually built a cabin on the land. Other families lived nearby, some who farmed, some poor

Danish immigrants who worked replacing ties on the railroad. Towards the turn of the century

the community of Mountain Dell was large enough to support a ward, dissolved in 1898 when

the city bought many of the homes to protect the watershed. Seymour Sr. kept the cabin as a

summer home. Dilworth’s father, uncles, and aunts brought their families here to camp each

summer, “usually about the 4th of July. We stayed until late August usually. We had a tent frame

on the bottom land next to the creek, and did our cooking in a two hole tin stove in the tent.” The

tents were suspended on wooden frameworks, over raised wooden floors. They slept on cots. The

men commuted fifteen miles to jobs in the valley, an hour-and-a-quarter by buggy, or stayed in

the valley two or three days at a time. Seymour often had company cars. One Overland that he

sometimes took to the canyon would quit without warning.

Father would get out, unhook the gasoline line and blow. The dirt would go back into the

tank and we would go until the dirt settled and was again in the line. Our lights were

carbide gas, and our horn was a rubber bulb. One pressed it and forced the air through a

reed. We had plenty of horses and wagons to look out for and of course always worried

that we might get hit by the Park City train as it wound its way up or down the canyon.

There were eight crossings and we were glad when number eight had been safely passed.

One of Dilworth’s early memories in Mountain Dell was of sassing his mother. After a

few unsuccessful warnings, Lou threatened to dunk him in the creek. He didn’t believe her and

sassed her yet again. “She picked me up by one arm and one leg and took me over to the creek

and dunked my head under it. I thought she was going to drown me. Scared me to death. That

cured me of talking to Mother like I shouldn’t.”

Louine says her grandfather kept horses at Mountain Dell and that the boys rode them a

good deal. She says they had trout from the stream for dinner nearly every day. One summer

Dilworth’s Aunt Elma read Les Misérables to the older children. Dilworth remembers

listening without really understanding. He tells of horseback riding, berrying (“wild currents,

chokecherries and serviceberries”), and grouse hunting, though he says he and Hiram never

hunted with the uncles, at least not much. “The camp was the most fun when our aunts were

being courted, and our uncles were courting.” Then, especially, there was singing around the fire,

“campfire fun and storytelling.” Grandfather Young would tell of his adventures crossing the

plains and on his mission. Seymour Jr., and Levi and Clifford (who both later became general

authorities) told of their missions as well. Phyllis Wells remembers how entertaining they were,

singing and joking and dancing and carrying on. Levi was known for his Indian stories. “Seme”

and “Lee,” she remembers, were both good mimics. Levi danced the Charleston with cousin

Florence Bennion, who was much taller than he. The brothers teased each other about their

“Chinese” names: Lee Young, Seme Young. They told Pat and Mike jokes. According to one, Pat

and Mike were parked on the fifteenth floor of a fifteen story hotel in New York City when a fire

engine went by below, then another. “Pat, come quick, come quick, they’re moving Hell and two

loads have gone by already.”

One night Lou found a nest of field mice in the cupboard where she kept Richmond’s

diapers. She called Clifford over. He, thinking to catch the mother, left the babies exposed in a

corner. Lou put out the lamp and went to bed, only to feel something crawling on her a few

minutes later. Carefully she reached up, lit a match, touched it to the lamp, and then flipped back

the covers. “Right there, lying on her nightgown, were three little naked mice. That mother

mouse had brought those mice in under the covers and deposited them on Mother’s lap.” Lou

called out for Clifford once more, who this time killed them.

On a Sunday afternoon once, when Dilworth was about seven, Grandma Young had

invited everyone down to dinner in her cabin, when a cloudburst hit Little Mountain. Before long

a wall of red, muddy water hit the cabin, picked it up, and floated it a hundred yards down the

river, where it wedged against the brush and willows. Water flowed through the house two feet

deep, so those around the table climbed up on it with the food. Dilworth ran up the stairs toward

the attic and watched from above. “No one was hurt, nobody drowned, and the water soon

subsided again, and then of course we had to be lifted out onto the higher bank, [with] mud

everywhere. And finally around about 8:00 o’clock that night, they sent some carriages up from

Salt Lake and took us home [to the valley]. All the bridges were washed out. They had a real time

getting up and down.” The tents were washed away. Dilworth says he learned never to camp in

the river bottom, as storms even several miles distant could mean flash floods downstream.

When they rebuilt the camp, they put it on higher ground. “If we’d have been in those tents . . .

every one of us would have drowned.”

Dilworth and Emily graduated from Lowell Elementary in the spring of 1911. Seymour

had the money to send just Emily (perhaps because she was oldest) to the Latter-day Saint

University, the Church-run, combination high school-junior college, located east of the Hotel

Utah. Dilworth presumably would go to Salt Lake (later West) High. “I felt terrible. I had just

turned fourteen and to be left out seemed to me awful. So I cried a lot, and Father somehow

raised the extra money needed to pay my tuition.” He remembers wearing knickerbockers to

school. He says he did well enough in English and history but that “Latin and algebra were

beyond me.” That year Seymour’s health turned bad. “He wasn’t right down, but he was miserable

for some reason . . . He thought he had kidney trouble, and he probably did because that’s what he

died of.” Seymour resigned his job, and that April, before Dilworth could finish his school year,

took the family to Mountain Dell while he recovered. “We couldn’t afford to live anywhere else.

We had no money.” School was not really an option–certainly there was none in Mountain Dell.

“Grandma Young helped us to get food, I guess . . . We ate food, I don’t know where it came

from.” They slept in tents through that summer and the next, spending the winter of 1912-13 in

Uncle Mel Well’s cabin, “which was better than the others, although it was unlined for winter

use.” That meant just a board between them and the weather. Dil says, “We learned what living

in an unlined cabin was–it was awfully cold.” Lou hung drapes–she writes in her history of an

evening when a cup of water froze three feet from the stove.

Other families had been around during the summer, but with winter here, the Youngs had

the camp to themselves. The children skated on a pond. The Youngs made a little money

pasturing horses for some men from Garfield. “Twelve head or so wintered over the high ridges

west of the camp and we could count them. In the spring we finally got to them and discovered

that one had a colt. Herding them was fun, although we knew little about how to care for them.”

Louine remembers standing by the train tracks and picking up coal one of the engineers would

throw off for them. She says her mother put their foodstuffs on the table at night, away from the

mice, and wrapped them in blankets to keep them from freezing. Relatives visited occasionally.

One day in February, Dil remembers, Uncle John Robbins came up on a sleigh.

It was a warm day and the cabin had got warm through the roof and we didn’t have a fire

in the stove. Uncle John got out of his sleigh and he came in and he says, “My, I’m cold!”

He went over to the stove and rubbed his hands on it and he got warm, and after he got

warm Hi said, “Uncle John, open the stove door!” Uncle John opened the stove door, and

there was no fire.

George Knepp, a strong, well-liked, good-natured fellow, not LDS, who ran the city farm

farther up the Dell, visited more and more often. George, later chief sheriff’s deputy in Salt Lake

County, could play the mouth organ and call country dances. Dilworth did not realize it at the

time, but George was courting Emily, and they married a year after the Youngs returned to Salt

Lake. Once Dilworth took the “bobs” to town “and was too ashamed to drive them through the

mud, so I took the wagon back.” Once in the canyon snow he found the sleigh’s tracks were

narrower than the wagon’s. He drove the horses four miles before they gave out with two miles

still to go. George “came along, and with the tongue of his bobsleigh pushing against my tailgate,

literally pushed me into camp. I learned there that false pride is a foolish thing. George never

rebuked, just laughed and pushed me home.”

The second August in Mountain Dell, George got Dilworth a job pitching timothy hay on

the Hugh Evans farm in Marion, not far from Kamas. (George pitched at the Wotstenholm ranch

nearby.)

It was my job to . . . hitch up and haul hay for ten hours each day, milk five cows and feed

them and the horses. The end of my first day found my muscles so sore that I could not

hold my knife and fork if I had to put pressure on them. Mrs. Evans cut my meat. By the

end of two weeks I was over my soreness and secretly felt my muscle each night and was

pleased with its hardness. I consumed tons of food and must have eaten a pint of

whipping cream each morning. I slept with Alva Evans upstairs and felt a little prickly at

first. I did not realize it was bedbugs, but it was.

Dilworth remembers the Evans boys ran wild, especially on Saturday and Sunday nights, “but I

never did indulge.

They all had horses and buggies and took in the country dances for miles around. These

were long lasting, followed by buggy rides home with the girls. Often they would race

buggies down the turnpike road, which had quite a high center. It is a wonder they were

not killed . . . At the end of the first summer Mr. Evans said, ‘Dilworth, you cannot do a

man’s work, but you are so willing and tried so hard I’m going to give you a man’s pay.’ I

got two dollars per day for thirty days work.

By that fall, Seymour had recovered enough to open a real estate office and move the

family off the mountain to a home at 2002 South 13th East. Mountain Dell became once again

just a summer retreat for the Youngs, until condemned for the new dam and flooded in 1917.

Chapter 2

Coming of Age

Granite Years

One day that winter Dilworth, now sixteen and six feet tall, went “uptown,” presumably

on foot, to LDSU to ask if he could finish the half-year he had missed. Osborne Widtsoe, the

principal, told him he could. Dilworth asked, “‘Well, could I do it on the money I paid on that

year?’ He said, ‘No, you can’t do that. You have to pay a half-year’s tuition.'” Dilworth had no

money, and neither did his father, so that was the end of that. He thought to try Salt Lake High

School, but the school had a rough reputation, and in any case, Granite was closer to his

Sugarhouse home. So he walked the thirty-five blocks out to Granite High and up to the third

floor to the registrar’s office. He told the man in the window of his project of finishing the half-

year, adding that he had no money for entrance fees. Willard “Wid” Ashton, a math teacher who

had been filling in for the registrar, enrolled him in the freshman class, explaining there were no

fees. Dilworth signed up for English, algebra, agriculture, history, and physical education–

Ashton taught this last. He asked Dilworth if he would like to sign up for seminary. “‘What is

that?’ said I. ‘It’s a class you take in your spare time given by the Church for no credit unless you

study the Bible,’ he replied.” So it was that Dilworth took seminary the second year it was ever

offered.

“Those were happy days.” Dilworth walked the three miles from home and back again

each day. “I had no money to ride–rain, snow or shine.” Many of the students lived on farms and

were a year or two behind, like Dilworth, from staying out to help at home. Adam S. Bennion,

later an Apostle, served as principal. Dilworth remembers him and Wid Ashton as “high

principled men [who] always insisted on high ideals in the students.” He adds, “I enjoyed the

school dances, and the girls were especially nice.”

Dilworth made a lifelong friend in Merlon Stevenson, later head of engineering and math

and head coach at Weber College and Dil’s neighbor in Ogden. The two had much in common–

both had been out of school, both walked long distances each morning and night (six miles for

“Steve” at one point). Both liked sports, worked and studied hard, and had high standards. They

resembled each other, too, at least enough to confuse their teachers. “Ike and Mike, they look

alike,” reads a caption in the 1915-16 yearbook. The picture of them together shows them with

similar haircuts, in similar jeans and drooping, long sleeved shirts. They have similar pointed

noses and similar jawlines. Steve says Dilworth was two inches taller and two pounds heavier.

He remembers the two of them sitting in Wid Ashton’s math class when Wid wanted to make a

point about perspective. “He said, ‘Well, a lot depends on the way you look at something,’ and we

kind of looked at him–‘What?’ So Wid came down and he had a book in his hand.” Steve was

sitting just in back of Dilworth. Wid showed the two of them the book and said, “‘Now, what is

that?’ and we both spoke up at the same time . . . but one of us said it was a rabbit and the other

said it was a duck. The bills for the duck were the ears to the rabbit, depending on which way you

looked at it.”

Steve thought Dil “as honest as the day is long, and that when he told you something you

could depend on it.” He thought him “just a good, solid American boy with high ideals, because

everything that we talked about was on a high level . . . I never in my life heard him ever use any

foul language or ever tell anything that was even shady.” They had fun and kidded each other, but

perhaps having had to stay out of school made them more serious than they might otherwise have

been. Steve remembers many of their conversation turning on lessons and helping each other

along. Wid Ashton noticed their hard work and counseled them to keep at it, to prepare

themselves well and then decide what they wanted to do and go at it. “Now I think both Dil and I

listened very carefully. I know I did, and I’m pretty sure he did, too.”

One year Dilworth talked Steve into taking a public speaking class with him. Steve,

raised on a farm, recalls that speaking was not his forte, but he went along. Miss Wolfe, the

teacher, apparently learned late of a division extemporaneous speech contest to be held at LDSU.

Rather than have Granite unrepresented, she got Dilworth and Steve to go. Steve recalls it was

Dilworth who persuaded him. “I still can’t account for how I even agreed.” Topics were to be

assigned from a list three minutes before each speech was given. The other schools had all had

the list for weeks. Granite’s representatives were obliged to wing it. Steve recalls his topic was

“The Mosquito.” Dilworth’s account does not mention his own. Steve says he “felt that Dil did a

fairly good job,” but calls his own performance a “fiasco.” Dilworth writes, “I did poorly. Steve

opened his mouth in his turn but no sound came forth.” For their trouble the boys were awarded

debate team letters. The winner of that year’s contest: Wallace F. Bennett of LDSU, later a United

States Senator from Utah.

Dilworth speaks of taking plane geometry from Wid Ashton, “to his despair, because I am

not a mathematician.” He says he played basketball under him his first year there. “I was like a

fence rail in width . . . Whenever I would get in the practice, within ten minutes my legs would

be so numb I could not feel them. The coach . . . would say: ‘What’s the matter, Young, you

baking?’ I would admit I was, a little ashamed of my weakness, and he would bench me for the

next fifteen or twenty minutes. He knew what was wrong, but I didn’t. I was growing so fast I had

no reserve strength.” That summer he returned to the Evans farm, stronger and better able to pull

his weight and happy to pay back Mr. Evans for his confidence the previous summer. He and

Lloyd Evans loaded one wagon against Alva and Dean Evans–“almost grown men. The first year

we could not keep even, but the second year we made them sweat to keep up. This was a source

of great satisfaction to me, and I came back home that fall able to keep up on the basketball and

football teams without ‘baking out.'”

Dilworth tried ranching the summer of 1915 when “a herd of cattle went past our place.

Twenty-first South was a trail street from the stockyards on 8th West and 21st South to

the mountains. These were wild Nevada cattle and dangerous. Get off your horse and you

were liable to be charged by a cow or a bull. They belonged to Heber Bennion, and he

was trailing them to Chalk Creek to the summer range. He had bought them from a

rancher named McMillan. He, his son Heber Jr. (grown up), a McMillan boy and . . . a

real Texas cowpoke . . . named “Big Jeff,” were doing the trailing. I had a pony old and

tough, and I asked for a job. Mr. Bennion hired me to help with the herd.I started out–no coat, a hat, the pony. We drove into Emigration Canyon for the night and

bedded down at Little Mountain. It was an all night herd job. Next day we went over the

Little Mountain trail up Killyon Canyon to Parleys Summit. We lost nearly 200 of our

500 in the oak brush in that canyon, and I lost most of my shirt and my pants in the same

brush. I learned why cowboys wear chaps and, too, why they swear at the cattle. We

didn’t have enough punchers, enough food, enough anything. We bedded the second night

on Silver Creek. By that time I was so tired that during the night I became obsessed with

how to spell “cattle.” I tried all night but had no peace until daylight when I stopped and

wrote it in the dust where I could see it.Two days later we turned the cattle loose on Bennion’s range on Chalk Creek–up near the

Blue Lakes–and I ate one last breakfast of four eggs and bread and started home. I don’t

know how many of those lost cattle were ever recovered . . . I, who had never chased

anything faster than a milk cow, really had my eyes opened to what a range cow can do.

The McMillan kid had a good horse and a bullwhip. A bull was lying down and

McMillan popped him with the whip. Before McMillan could get his horse moving, that

bull was on his feet, charged, and had gored the horse in the hip. That ended the horse–

and the boy went home.

Big Jeff was in town a few days later and telephoned Dilworth to see if he wanted to go to

a show. The Youngs had him over to dinner, after which Dilworth and he went into town. Big

Jeff wanted to stop at his hotel to get something. Once there he tossed a manila envelope on the

bed and, while he went into the bathroom, invited Dilworth to have a look. Inside were a dozen

glossy prints of “naked women, in what they thought were striking poses. I saw what they were,

quit looking at #4, and put them back in the envelope.” They went to a movie, with apparently

nothing more said. Afterwards Dilworth “bade him good night” and went home. That was the last

he ever saw of him.

I suppose he expected me to go with him to a bar, have a drink or two, and then seek out a

house of ill repute . . . I realize now that I could have been in great danger, but somehow

he sensed I was not the kind of boy who did bad things, and perhaps dinner at our house

taught him a different culture than he was used to. He was a profane man but not meaning

to be. It was all he knew, apparently, and I thought there was an innate courtesy in him

that is in few men who work with their hands today.

When Dil had been an eighth grader at Lowell, an older boy had come to the playground

and shown some of the boys a couple of pictures. “I saw only one of them. It was the worst sort

of pornography that one could imagine. He strutted and bragged how he was indulging in the

same stuff . . . It was terrible. I would like to forget it, but it lingers. It taught me that if I don’t

want to have it in my mind, I must not look.” This became Dilworth’s characteristic response.

Louine remembers walking in Sugar House with Dil when they passed a group of teenagers

having a lawn party. “They were playing kissing games–‘wink’ was the popular one at the time.

Dil hurried me on, even though I wanted to linger and watch the excitement. ‘No!’ he said. ‘Kids

should not play games like that, playing with the emotions!”

Dilworth writes in his history of rummaging in a chest of drawers in the attic when he

came across two large leather-bound “doctor books.”

One contained the anatomy of women, especially sex organs. It was well illustrated with

drawings of the process of birth, from conception to entry into the world. It also described

instrument delivery and even what must be done if the baby’s head was too large to enter.

The second book was about marital relations, and while not entirely accurate in some

details, was interesting reading for a fifteen year old boy.

Dilworth notes, “We never asked [Father] anything about the facts of life and he never offered to

tell. His only attempt was the night before I married Gladys, and then all he said to me was to

remember that I was a gentleman. I nodded and agreed.”

It would have been a lot better if Father had instructed us in these things. It is odd to me

that parents could assume adolescents would not be curious, but they were raised that

way. It was hush-hush, but I suppose too that I personally was none the worse at the

moment. Yes, I was too, for I often came back to those two books that year, and I am sure

they indelibly impressed me like a phonograph record, constantly played, does. I am sure

I thought too much about what I read–not analyzing, just caught up in the sex emotions it

stirred up. Yet I did nothing physically–just imagined.

Dilworth writes that herding on Little Mountain “cured me of wanting to be a cowboy.”

Yet he gave it one more try in 1916. George Knepp, who managed Utah-Construction-Company-

owned ranches, got Dilworth a job on the Big Creek ranch, near where Utah, Idaho and Nevada

meet. Dilworth traveled to Rogerson, Idaho, where he saddled up a company-owned riding horse

and rode forty miles to the ranch. He doesn’t tell of this stint in his history, but he mentioned it in

speeches and around the dinner table. As a general authority he would explain the Lord’s

seemingly contradictory instructions to Adam and Eve in the garden by alluding to the mule

teams on the ranch that, no matter how much you yelled and whipped and tugged on the reins,

would not move until you swore at them. So too the Lord had to get the Man and the Woman

moving by speaking a language they could understand. Dilworth learned the language, but found

it easier to start swearing than to stop, and he never completely overcame it. “Vulgar talk is a

great temptation,” he said at a BYU devotional one time. “Little half-swear words, the damns and

the hells, I guess, come easy. They’ve done to me. I punched cattle once and discovered that cattle

didn’t understand any other language. But I wish I’d tried the other language on the cattle. They

might have learned something. And I would certainly have saved myself trouble.” The cowboys

sang to the cattle to keep them from spooking at night. “Yippie-Ki-Yi-Yo” was one of the songs.

Dilworth’s boy scouts would later sing its innocuous first few verses. Dilworth discovered the

song had a hundred verses, ninety-five of which were filthy. He never mentioned going out of his

way to learn any of them, and yet, as he told it, they continued to visit him throughout his life, in

the least convenient of places, such as in meetings in the temple, and that all he could do was

chase them out.

Emily remembers Dilworth calling her “his best girlfriend” and taking her to mutual

dances. Louine, quite a bit younger, remembers the way he managed to get Rich and Hi to do his

chores, sometimes trading books for the work. Louine he simply charmed into shining his shoes

and helping him get ready when he went out. “I remember pressing his pants time and time again,

and how I loved doing it.” She remembers, when she was very small, him sending her after

glasses of water while reading. “‘That’s only a sample! Please bring me another,’ he would tease

as I cheerfully trotted back and forth to wait on him.” Dilworth was sociable at school and

enjoyed walking with a large group of friends, male and female, including Wid Ashton’s sister,

and sometimes Wid. In his history he writes, “Those walks to and from were the best part of

school.” Most his group belonged to Forest Dale Ward, and Dilworth began to attend there, too.

After a time he was called to teach a Junior Sunday School class. “I enjoyed that, although I can’t

remember making great preparations.”

Dil’s father, when he came down off the mountain, did not return to church. Perhaps he

was afraid of callings because of his poor health. Perhaps he had gotten out of the habit at

Mountain Dell and on subsequent long visits with Emily and George on the ranch. Perhaps he

was embarrassed over not keeping the commandments–this is Louine’s opinion. “Father and [one

of her uncles] were close companions, and they broke the Word of Wisdom by enjoying their

cigarettes. Father had his cup of coffee each morning, but he never let us see him smoke. He

talked about having a taste of wine with Thanksgiving dinners, which he said was not breaking

the Word of Wisdom. My mother was saddened by this, but she did miss church on Sunday, but

did remain active in Relief Society, at least to be a Visiting Teacher.” There may also have been

an element of disappointment or bitterness on Seymour’s part over being passed over. He was the

oldest son. His father and grandfather had both been First President of the Council of Seventy. In

1909 his younger brother Levi was called to the Council. In 1941 another little brother, Clifford,

was made Assistant to the Twelve, with authority higher than the Seventy. According to

Dilworth’s widow Hulda, this is the reason Dilworth gave for his father’s staying home.

Louine remembers their father during these years as compassionate and given to service.

“He was very thoughtful of neighbors, friends and relatives, visiting and cheering people. Often I

helped him compose or correct letters of appreciation and encouragement to others.” She

remembers him as “solicitous of his own family, especially visiting and offering help for his

invalid sisters (one deaf and one lame, and one completely incapacitated.)” She remembers

family prayer and religious discussions around the dinner table. Her parents did not get around to

arranging her baptism until she was eleven, but like the other children, she attended church and

auxiliaries, and she feels her parents must have given her some encouragement. One summer

when the family visited Emily on the ranch, Hiram held Sunday School for the children.

One day the bishop of the Forest Dale Ward told Dilworth he would have to release him

from his call. He said the policy of the Church was that members could only hold callings in their

own wards. He said he was unable to advance him in the priesthood, and told him he ought to go

back to his own ward.

My ward, Richards Ward, was new and was at first meeting in a tent on the property of

Willard Richards, 9th East and Hollywood. Later a chapel was built on Garfield between

8th and 9th East. But I was shy and strange and told the bishop that if I could not go to his

ward I would not go at all. He said he was sorry, advised me to be obedient, released me

from my class, and walked away. I was stubborn and scared and so I went home. I didn’t

enter a meeting house again until I was eighteen years old. I did no wrong things. I stayed

home, read a great deal, visited my cousins up on the Avenues on Sunday afternoons, but

attended no meetings . . . My father was not active and my staying home, keeping out of

trouble, did not seem to bother him.

Hulda reports Dilworth spoke of having read the Scriptures, A Comprehensive

History of the Church, and every other Church book he could get his hands on during his two

or three years away. In his history, Dilworth reports, perhaps with some bitterness, that no one

from his home ward tried to reclaim him.

Ward teachers came and went; they paid me no attention. The bishop, if he had ever heard

of me, gave me no signs . . . Knowing my disposition, I am sure if anyone had put forth

the helping hand, been interested, invited me, I would have gone to Church, but I didn’t

have the courage to break the ice myself . . . My father should have. My ward leaders

didn’t think it to be their responsibility. We were classed as an inactive family and to be

left alone to stew in our own juice.

At age eighteen Dilworth made up his mind to return. He went to the ward and introduced

himself to Bishop J. A. Rochwood, who assigned him to the priest quorum, though he did not

hold that office. “If he had put me with the deacons, I would probably have quit again.” Soon he

was ordained a priest. He attended his meetings faithfully. “Hi and I were often the only two at

sacrament meeting to administer the sacrament.” He says he liked to talk to girls on the back row

during the meeting. “I realize now I was a nuisance doing it . . . I blithely went on having fun, not

conscious of the offense I must have been to the people in the rows ahead of me. I suppose I got a

bad name for it, but . . . no one called me in and corrected me. I would have quit in a moment had

I realized. I was a noisy boy growing up.” Dilworth later spoke of one Sunday simply deciding to

listen. He concentrated on the speeches, meditated on them during the sacrament, felt the Spirit

and left the meeting exuberant.

Dilworth dated Morris Knott, a Methodist girl. “During my senior year, I took [her] to the

school dances three times, which was tantamount to saying you were pinned.” He visited her at

her home one Sunday, where they sat on the porch swing looking at the family photo album. At

5:00 she invited him to church, and he went along. “It was a nice service. No kids cried, the

minister was young and a good speaker, the music soothing.” Afterwards Mrs. Knott invited

Dilworth and two other couples to her home, where she served ice cream and cake, then brought

coffee to all but Dilworth. “She said, ‘I know you do not drink coffee, but I have milk, root beer,

pop. Please name it.’ I took root beer. My large glass was the envy of the other boys against their

demitasse cups.” He left at 10:30, “as all young men did,” and walked three miles home.

The moon was out, the night romantic, and I liked that girl. But I thought as I walked

along; and when I walked upon the porch at home, I made up my mind that I would never

take out that girl again, and further, would not go with any girl unless she was eligible to

go to the temple at the time I took her. I kept that resolve.

Dilworth dated Afton Love, one of the girls from Forest Dale, through graduation. Afton

had a fused hip and walked with a pronounced limp. Merlon Stevenson remembers few people

would pay any attention to her, and that Dilworth went out of his way to talk to her and make her

feel good. Dilworth writes, “She reminded me of Aunt Elma Young and I mistook sympathy for

love.” He came to the realization he did not love her enough to marry her long before Afton did,

and her feelings were apparently hurt. He found the situation painful and confided in Steve how

terrible he felt. But as Steve puts it, “His whole purpose . . . was to help make her feel good and

pay some attention [to her] . . . He had a heart of gold.”

Sporting News

“While at Granite I tried all the sports,” Dilworth writes. Track brought him the least

success. He ran the half mile once without training, leading until the last 220. “My legs went

numb and my eyes blacked out. I managed to finish but was badly beaten.” Merlon Stevenson

excelled at the high jump and pole vault. Dilworth says, “I liked the team games and played left

field in baseball but was poor at batting.” Steve, who proved a good athlete, remembers Dilworth

as a consistent player and modestly refers to himself as the weak link. Dilworth’s history

describes an encounter at the mound with Stanley Johnson, whom the papers referred to as “The

Terrible Swede.”

He was about twenty years old and pitched with man’s speed. He threw a ball at me and I

stepped back and it curved over the plate. He did it again. I resolved I would strike it the

third try. It came on–didn’t curve–struck me on the left cheekbone. I struck at it and was

declared out. My face was swollen badly but apparently it did not break bones . . . I was

just plain scared in that game, or I would have ducked the last minute.

He and Steve played football–without the padding of the modern game–both offense and

defense with few substitutions. The team relied a good deal on these two big backs. Wid Ashton,

coming off a championship year, scheduled a practice game with Utah Agricultural College. This

was the first varsity game Dilworth played. “We were big kids,” Dilworth remembers. “We were

as big as those college kids.” Probably several were nearly as old. Dilworth recalls his father as

nervous and tending toward over-protective during this period. “My father said to me, ‘Now, if

you get hurt playing football, you have to quit.’ He didn’t want me to play in the first place, and

the only reason he let me play was that I insisted.” The game was held in Logan. Steve was

fullback and leader, Dilworth halfback. Steve made a diving tackle at a player’s legs, hitting his

head against the player’s thigh pad, twisting his neck and passing out. When he came to, he

continued to play, but had little memory of it afterwards. The coach sent in word for them to

swap positions, but Steve couldn’t keep it straight and kept lining up at fullback. Dilworth says,

“He couldn’t remember where he was. If you told him what to do he could do it. So he’d say,

‘What shall I do,’ and I’d say, ‘Go out there fifty feet, and if anybody comes toward you, tackle

him.’ So he’d go out there, and if the guy’d come toward him, he’d tackle him.” Steve remembers